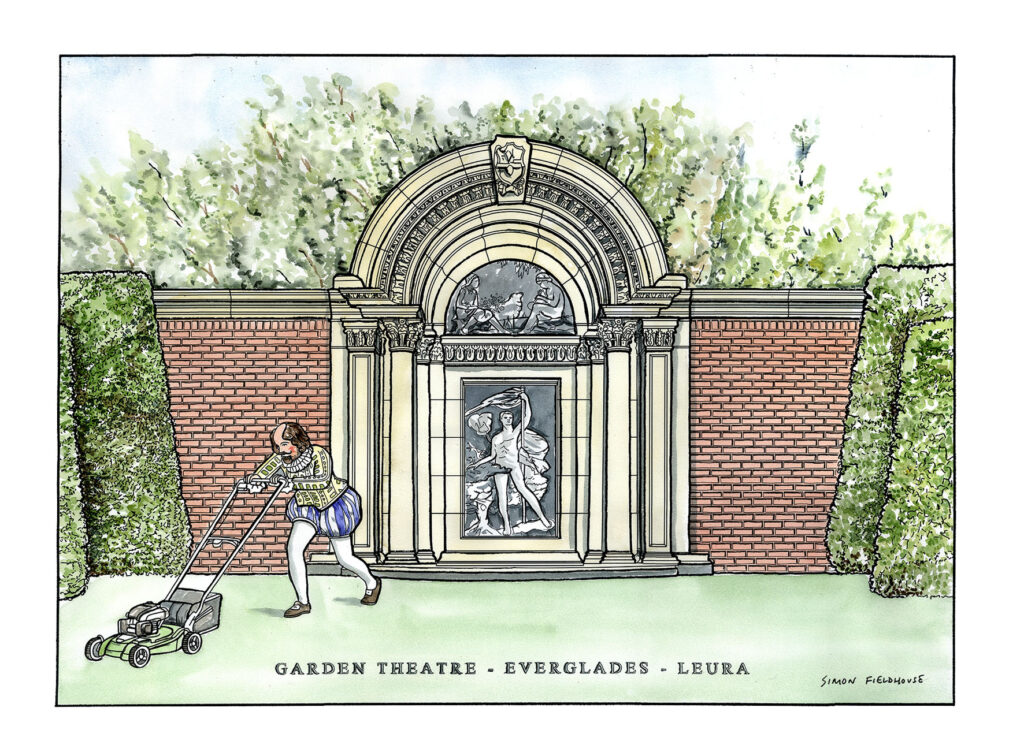

Garden Theatre - Everglades - Leura

Everglades is a heritage-listed former residence, art gallery, cafe and garden and now tourist destination, house museum and garden at 37 - 49 Everglades Avenue, Leura, City of Blue Mountains, New South Wales, Australia. The garden was designed by Paul Sorensen (possibly in collaboration with Henri van de Velde) and the design of the house is also attributed to Paul Sorensen; and built from 1915 to 1938 by Ted Cohen. It is also known as Everglades Gardens. The property is owned by the National Trust of Australia (NSW). It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 1 March 2002.[1]

As a regular visitor to the mountains he decided in 1932 to purchase Everglades which previously had been an orchard destroyed by a bushfire in 1910. Almost immediately he began discussions with Paul Sorensen regarding the garden he proposed to build. The work was eventually to be extended to include the design of the house as well as the garden. Van de Velde spent every weekend tirelessly working in the gardens, frequently extracting labor from his many guests. Sorensen estimated that Van de Velde spent thousands on the development of the Everglades and considered him to be the greatest patron of landscaping gardening that Australia ever had.[1]

Paul Sorensen (1890-1983) commenced landscape training in Copenhagen in 1902 with the final two years of his training under the direction of Lars Nielsen, a leading Danish Horticulturist responsible for the design of much of the open space system of Copenhagen. This period included maintenance work at Villa Hvdore, the summer place of Queen Alexandra of Denmark.[1]

In 1914 Sorensen decided to emigrate and left for Australia. He managed to gain a position as gardener at the Carrington Hotel, Katoomba and began remodeling the garden there before (by 1917) setting up his own nursery and garden design business in the Blue Mountains.[1]

In 1933 Sorensen met Henri van de Velde through a client R. J. Wilson of "Dean Park". Wilson encouraged van de Velde to buy the Everglades property and engage Sorensen for the design of the garden. At everglades he paid homage to the magnificent views of the Jamison Valley below and to the Blue Mountains beyond. The Terraces he constructed were accordingly aligned with the natural slope and to take advantage of the views in a way, which did not allow the scale of the scene to overwhelm the garden. He held that the form of the garden was more important than colour and considered that Australian gardens generally were only interested in colour with the result that the form was often neglected. Also unusual for the time was his retention of native species such as banksias and eucalyptus within the garden. As few nurserymen were at that time propagating native species, he tended to draw upon the palette of exotic species with which he had become familiar in Europe, many of them he supplied from his own nursery or imported from around the world for the particular project.[1]

Trees and shrubs were always seen by Sorensen as the most important elements of a garden and were always placed to create a feeling of mystery as to what was behind them, as well as giving the usual feeling of enclosure and shelter. The idea of development over time is a commonly recurring theme in many of his gardens and displayed a profound awareness of the ecological impossibility of fixing the character of a landscape permanently in every detail. The aim was to create a final landscape, which, although having different qualities of beauty at different times in its development period, would achieve a state of ecological balance in which its continuing maintenance would be relatively minimal. This planned continuity of change and development over many years was quite revolutionary when Sorensen began his work and even today is not always accepted.[1]

There is little visible evidence of the immense physical difficulties encountered in building the garden. Construction took place before the days of heavy earth moving equipment and consequently all earthworks and the movement of the heavy stone were carried out by manpower alone. Fortunately for Everglades, the Depression was at its height and manpower was readily available albeit unskilled.[1]

Sorensen saw the first task as deciding on the qualities of the site most desirable for retention. Existing trees were marked to be kept, only mishapen or damaged ones were to be removed. Sorensen must have been keenly aware of the opportunities to exploit the dramatic outlook over the Jamison Valley from the lower part of the site. The view of distant cliffs and valley floor carpeted with dense eucalpyt forest, all softened by the gentle atmospheric blueness so characteristic of the mountains, was one to stir the imagination of all but the most unromantic. Sorensen decision not to use this view as part of the formal garden but to limit intensive development to the area previously disturbed for the orchard was made very early in the design stage.[1]

The fact that this view could not be obtained from any of the formal terraces must have seem strange to many people, but this decision was in line with Sorensen's belief that it was wrong to be able to perceive the total of his design from any point and that element of surprise that would come from arrival at his lookout points would add an incredible quality of delight to the garden. He also realised that the grandeur of the scene was such that it would be out of scale with anything he could construct and that it was possible that any attempt to make this view a dominant feature in the formal part of the garden would detract from both the view and the garden.[1]

Apart from the problems of the slope, the other major difficulty encountered was the thinness and rocky nature of the soil. The very factors that made the Blue Mountains such a desirable destination for the holiday maker- the spectacular cliffs and the rugged grandeur of the scenery- created immense problems for the garden builder. The whole area was formed from sandstone, which belongs to the Narabeen group of Triassic sandstones. Much of the stones character comes from its richness in iron oxide which gives it its rich, dark red or purple coloured narrow bands and layers which, over eons have been warped by geological movement. The iron oxide makes the layers containing it much harder than the surrounding stone so that with erosion of the softer stone the so-called ironstone is exposed on cliff faces in quite incredible forms ranging from flat stones through curves to tubes. The soils formed from this parent material are very sandy, lacking in nutrients and full of the harder ironstone fragments.[1]

Sorensen turned this physical character of the soil into an advantage by hand-digging the whole of the cultivated area to the depth of 600–900 millimetres (24–35 in) and removing all ironstone found in the process, stockpiling it according to quality and colour and eventually for packing and filling. The walls formed from this stone exhibit an extremely high quality of workmanship. In many places Sorensen left pockets in the walls where he could plant small growing shrubs to soften the walls. The walls formed terraces filled level with soil, stepping down the slope to the lookout point, with the garden continuing down to the Grotto pool, created by the placing of a 40-ton rock in its present position.[1]

Sorensen was retained to carry out maintenance work on the gardens even when development work was not in hand. Work on the garden continued with an interruption due to the War until 1947 when Van de Velde died.[1]

Following Van de Velde's death the property was purchased firstly by Mr E. E. Bristow who sold to Mr Harry Pike, a grazier who in turn sold to Swain & Co. Pty Ltd, whose then principal Mr A. N. Swain was a garden lover.[1]

After acquiring Swain & Co, Angus and Robertson, Booksellers and publishers attempted to dispose of the property, advertising in Britain and Europe, in an attempt to attract a purchaser with sufficient means to maintain the garden. That attempt failed and it was aging offered for auction in Australia, but was again passed in. The National Trust purchased the property in 1962.[1] During this period of private ownership there was a gradual deterioration of the garden resulting from the lack of an enthusiastic owner/occupier and the loss of Paul Sorensen's services.[3]: 4 [1] During its era of private ownership there was a gradual deterioration of the garden from the lack of an enthusiastic owner/occupier and the loss of Sorensen's services. Everglades was one of the Trust's earliest acquired properties and the first with a garden. Members were invited to visit from 1962. From 1962-70 the Trust managed it directly, a period marked by unsuccessful attempts to exploit the place and uneven decline. In 1963 the Trust requested the NSW Government resume undeveloped lots to the south of Everglades. Approval was given in 1964. The Trust was appointed trustee in 1964.[1]